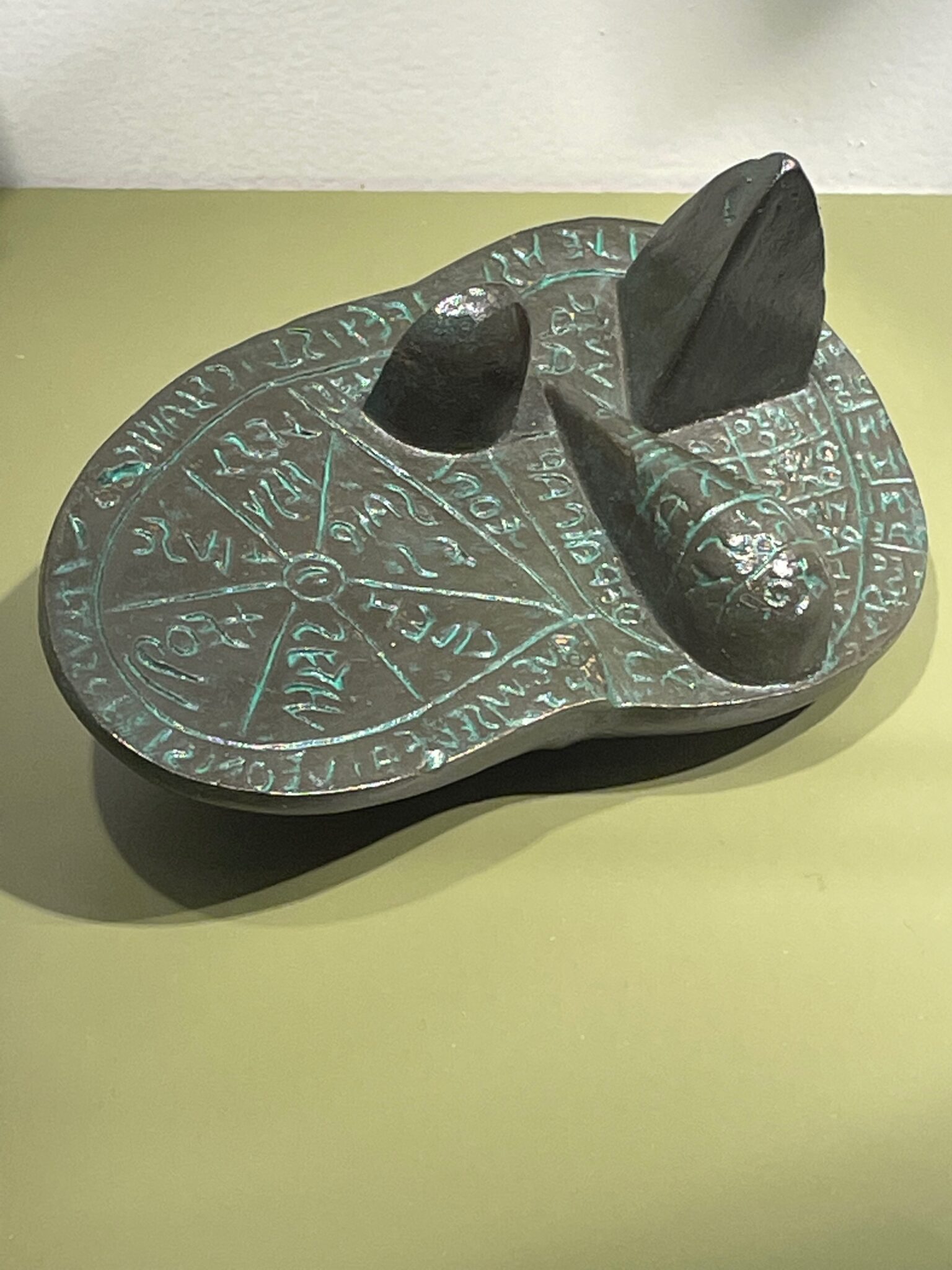

Liver of Piacenza

Notes from Meeting with Prof. Netanel Anor, October 15, 2021, Berlin, Clémentine Deliss

Netanel Anor works on Cuneiform culture, which emerged with the closure of pagan temples in Babylonia (today’s Irak) circa 300-400 BC. Today, the Cuneiforms constitute a controversial area in terms of provenance studies. Some historians refuse to publish work related to Cuneiforms that are held in private collections, because these collections may be connected to illegal excavations. Cuneiform script was originally invented to transcribe daily transactions, taxes, etc. In parallel, it led to the development of a lexicalist dictionary that could transmit the knowledge of the scribes. This is a time of pantheistic beliefs with an inordinate number of gods, often characterized by their locality, such as a city or an animal.

Anor refers to terms such as “station”, “weapon”, “finger”. These are part of oracular protocols and used to report what can be seen. These oracular protocols function as a tool of description and interpretation.

The oracle addresses concerns that are happening now, in the present and calculates the sum of observations. At that point one asks the oracle what to do next. Oracular experts were often appointed to the army as strategists, and it was usual for a King to consult several experts, especially if the result of the reading was indecisive. If that was the case, the ritual would be repeated. There was a fear of false information.

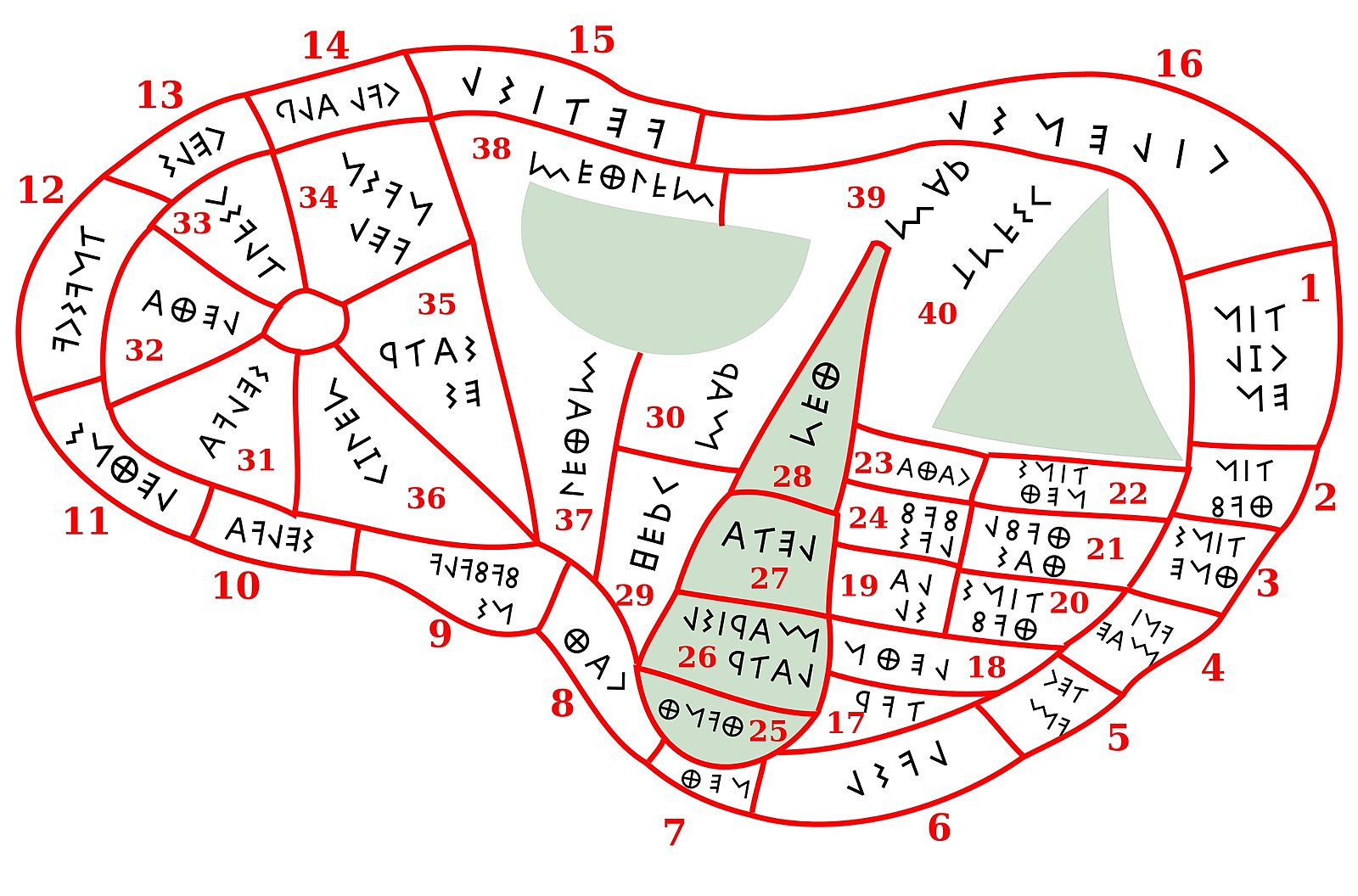

The diagram from Piacenza relates extispicy to astrology, connecting parts of the liver to zodiac signs, and is likely to be from circa 400-600 BC. The script is Etruscan. This is one of the best known representations of oracular liver.Following the Babylonian scheme, the liver is divided into zones that each have meaning. (cf. the publication by Stefan Maul, in which he lays out the terms.)

In many respects, the liver diagram represents a cartography, as if it were a representation of the city. One also says, “The liver is the reflection of the sky.” (Anor)

The liver presents a constellation of ominous signs which lead to interpretation.

The liver is the tablet of the gods and is polyvalent.

It requires the art of formulating a question:

– An exact question, e.g., what to do on the battlefield?

– A model question, e.g., related to health, the prosperity of the city, drought, climate change, in short, broader issues.

The oracle requires sacrificial material, for example, the liver, oil in water, or smoke. Smoke was seen as incense for the gods. Once this sacrifice has been performed, the gods respond.

The steps of the oracle:

- First a problem has to be identified.

- Then the question has to be articulated.

- The power (or God) who can address this question has to be ascertained? E.g., climate change: one addresses the God of weather; pandemic: one addresses the Goddess of healing. The Sun God is the final judge.

- Then one establishes the space (locus) and time of day to perform the oracle.

- Objects are identified and the way they are chosen is important.

- A prayer is performed. (Netanel has agreed to recite an Arcadian prayer from Babylonia in the MM-U Debating Chamber at KW.)

- A sheep is slaughtered. Or oil is poured into water.

- The answer to the question, the verdict, is revealed at dawn when the sun comes out.

- The meanings of the objects are discussed. Parts of the liver may be the enemy, other parts, good.

- Each object is given a value.

- Objects are evidence.

– Ominous signs: phenomena. Is a particular phenomenon ominous or not? An example of an ominous phenomenon is an eclipse.

– The oracle works through conditional sentences (Shuma phrases)

– An ominous object has a meaning beyond itself, a generative quality of signs.

Conclusion: In our discussions, Netanel and I looked at the possible correlations between the notion of the prototype as generative, unfinished, evoked in the conditional, and the ominous object of an oracle.

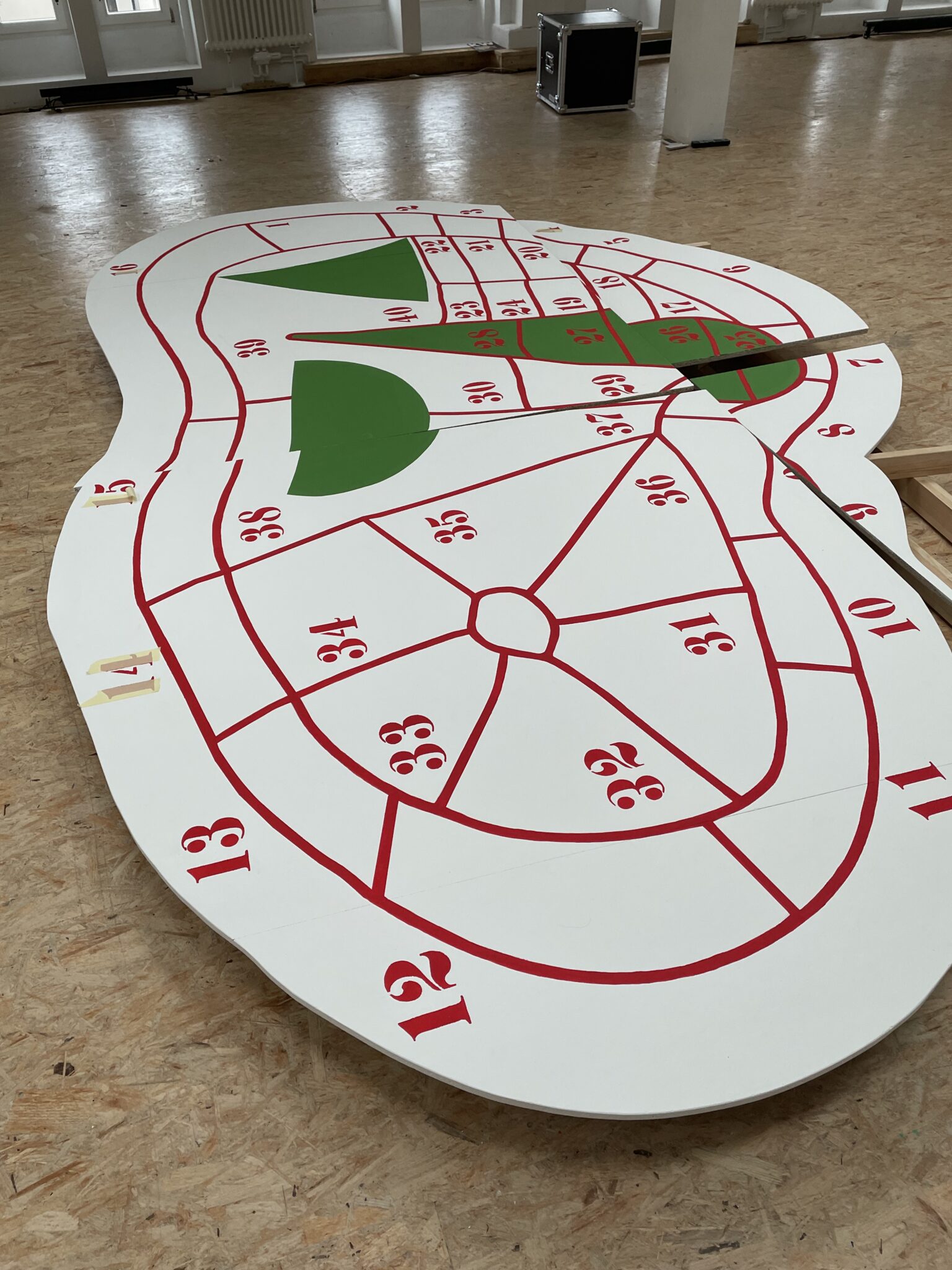

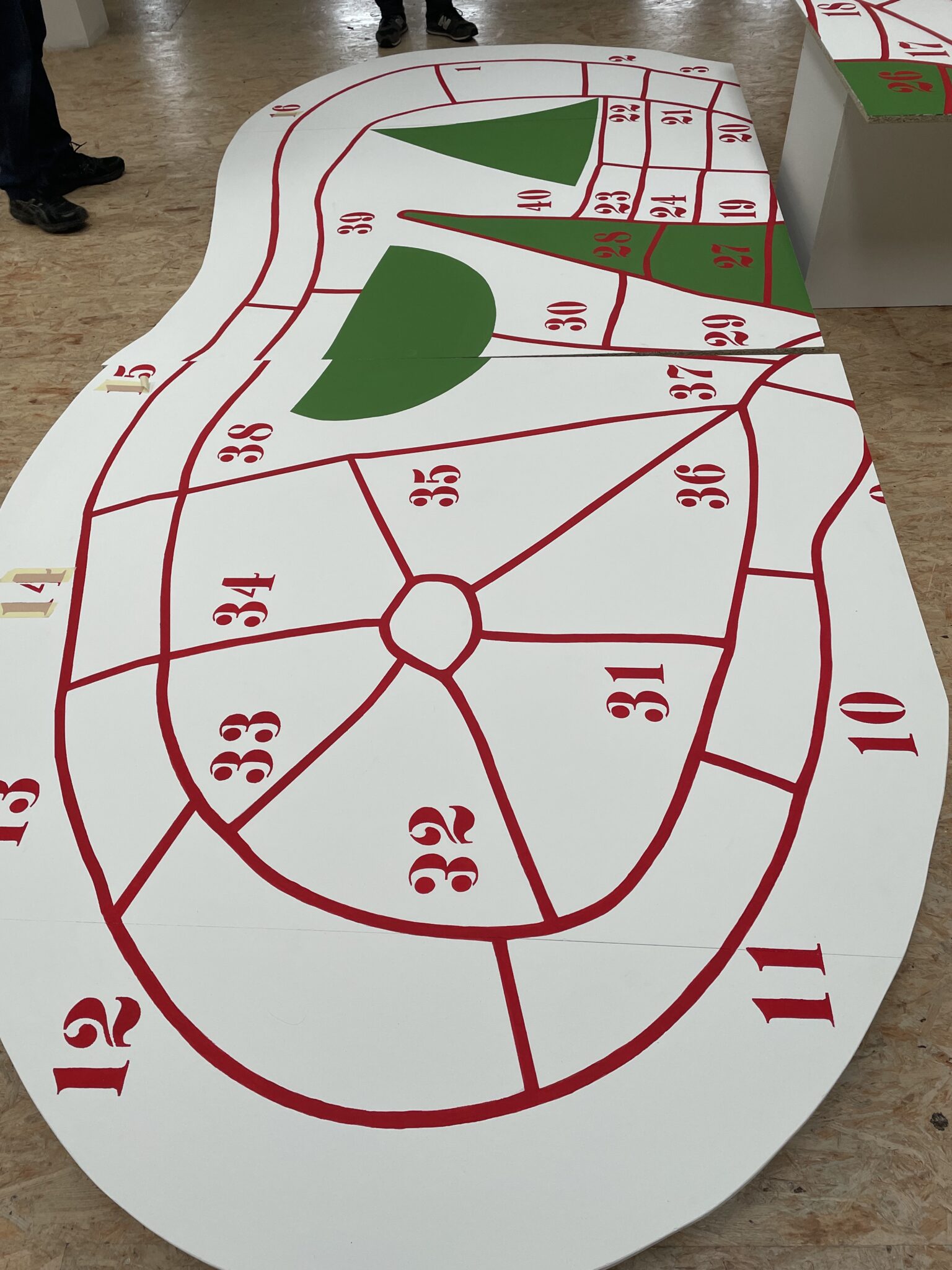

The oracle could provide a hermeneutic choreography: a dramaturgy with which to elicit meanings from ominous objects (prototypes) that we place in constellation to one another.

Interesting too, is that this process provides a tool for the description and interpretation of what one observes, an exegetical format, which is not the same as that of classic contextual prose.

I could imagine that towards the end of the Debating Chamber, perhaps following the Responders comments, we would look at the prototypes as if they were ominous objects. A sheep’s liver, and oil in a basin of water (watching the moves of the oil and the direction it takes to the person holding the basin), could give the verdict on our question/questions. I think this procedure could be helpful in getting us out of an academic, disciplinary impasse of specialisation.

Notes in response to Clémentine Deliss from Netanel Anor:

- I did not mean to say that the oracle deals only with the present. What I meant to say is that the oracle does not only address questions about of the future. The oracle question deals essentially with a problem, and as such often has to do with those concerning the future; an example can be: “will the military campaign be successful?” But sometimes questions refer to the present “is my brother now on the run and joining my enemy?”, or the past, “was I betrayed by my officials?” in other words, the question focuses on a problem, often related to future events, and questions on how to act in the future. It can also concern what is happening just now.

- You seem to struggle with the term “oracle expert”. You put some question marks next to it. The term in Akkadian is bārû, which literally means “seer”. This expert deals with what is often called “provoked divination”. This means an expert that comes with a problem, formulates a yes/no question to the gods and finds the answer during a ritual or an oracle process. This is unlike another field of expertise, that of the “astrologer” (Akkadian: ṭupšarru) who is an expert in unprovoked divination. He does not articulate a question nor does he perform a ceremony to evoke oracular signs. This kind of expert stays put, rather, and watches the skies and wait for ominous signs to appear in the sky or on the earth. Also, the analysis of unusual births (especially of animals), seen as ominous, is among their duties. Both experts deal with what we call “divination” but do different things (at least from an emic perspective) and this is why I usually refrain from using the term “diviner”. But you can often find it in the literature and use it, if it suits you.

- As for the liver of Piacenza, it stems from the Etruscan culture which preceded the Romans (this is what I meant by 6th century BCE) in the area of Tuscany. But I think the object itself dates to later periods, 2nd or 3rd century BCE. The inscriptions are of theonyms related to stars and constellations, but the exact readings of the inscriptions on it are disputed as far as I know.

- As for the term omen and “omen literature”. The term omen is usually thought of in English simply as sign sent by the gods. Ancient Babylonian scholars gave great significance to such signs. Therefore they were eager to detect them and saw these signs almost in every phenomenon possible. As the art of interpreting the signs was seen as a scholarly discipline, the scholars in Babylonia dedicated much energy in organizing the knowledge they had about these phenomena in the form of manuals or handbooks, generally referred to as omen compendia or omen series. In these handbooks, each omen (phenomenon) was recorded in the form of an omen-sentence always formulated as a conditional sentence: “if so and so, then so and so” for example “if the gall-bladder is red, the king will die in battle”. These sentences where collected thematically and were written one after the other to form encyclopaedic or encyclopaedia-like compositions, as with the above mentioned omen-compendia (or omen-series). We hence find clay tablets recording for example, a compendium of oil-omens or other tablets recording eclipse omens or liver-omens etc. Abraham Winitzer composed a detailed book on the principals of this type of handbook. It is rather detailed and complex to read.

- To the Debating Chamber you are preparing for November. In my opinion, the event can nicely be equated or paralleled to an oracle procedure, as one can certainly say that such a procedure was done in a dramaturgical setting, or in the frame of ceremony. In order to keep the event within the frame of the oracle-procedure metaphor, the following points have to be stressed as crucial and be elaborated:

- identification of the problem

- articulating a question, preferably in a form of a “yes/no question”.

- creating a setting where phenomena brought forth are examined and given a type of value allowing us to address the question.

- creating a process in which the participants are can reach a final decision or verdict concerning the main (“oracle”) question, while assessing the observed phenomena, (preferably) as a set of evidences with positive/negative values.

- In case you wish to see further on how an oracle question can look, or if you are interested to know more about other oracle techniques, etc., you can go to the following. The first is the book by Stefan Maul from Heidelberg. It is a book about divination written for the general public with very nice descriptions of the procedures and how they were done . The second book is a survey of all the cuneiform sources dealing with the different venues of divination (including astrology etc.) written by Ulla Koch who lives in Copenhagen. Also here are the links to the pictures of liver models from Sippar and from Borsippa:

- These are only two examples among many liver models in the ancient near east. But these are the nicest and most well preserved. They also beautifully show how the liver was thought of in terms of a matrix. This reminds me also that there are two books on the subject of liver models, now when I think of it. One by Meyer, 1987: Untersuchungen zu den Tonlebermodellen aus dem Alten Orient. There is also a book on Models in Anatolia by De Vos 2013: Die Lebermodelle aus Boğazköy.